For centuries, the question of whether photography belongs to the realm of the document or of art has haunted its history. André Rouillé, in Photography: Between Document and Contemporary Art (2009), makes this clear: from 19th-century police archives to late-20th-century conceptual installations, photography has never been univocal. It has oscillated between evidence and fiction, between objective record and poetic construction.

This tension is not a weakness but its strength. As a document, photography preserves traces, organizes collective memory, and testifies to what has been. As art, it becomes a device of imagination, capable of producing possible worlds. The mistake would be to confine it to one pole only.

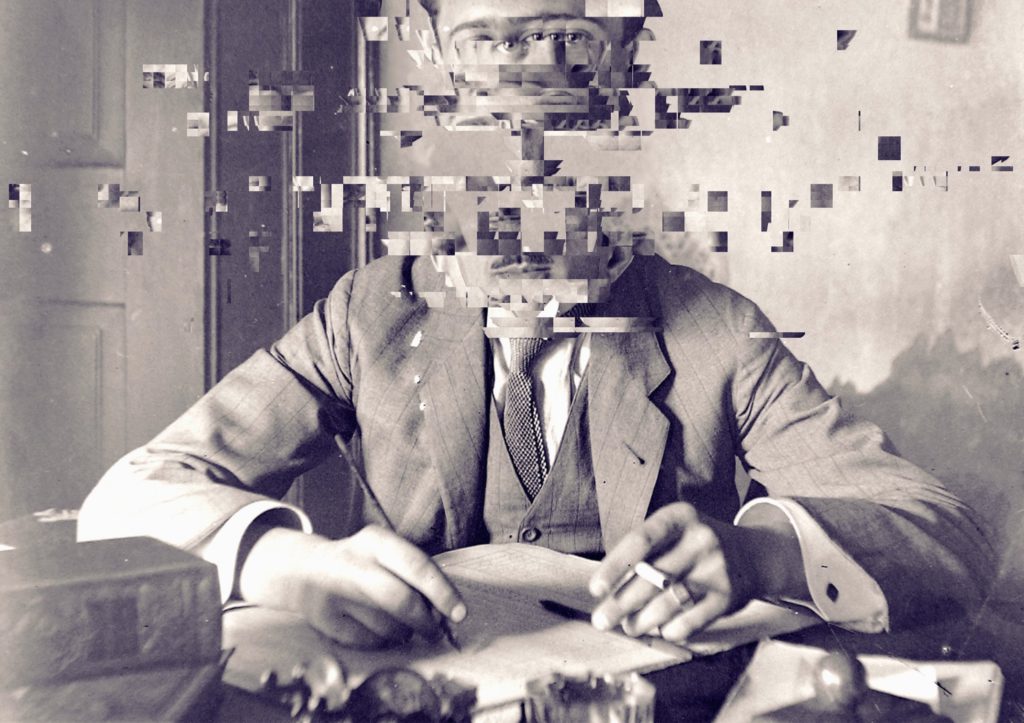

Today, in the 21st century, this debate is reshaped by the digital. Memory no longer resides only in family albums or state archives: it circulates on networks, fragments across servers, and expands through algorithms. Technology, then, is not a demon deforming experience but a catalyst—accelerating the production of memories, multiplying the modes of seeing, and transforming how we share images.

Catalyst means it does not replace human memory but precipitates it into new configurations. A photograph is no longer just the trace of a moment but the node of a process: collected, intervened, and refigured across contexts. What matters is not the tool itself, but how we design the process, how we care for provenance, and how we open space for the image to remain alive.

Contemporary photography shows that memory and technology do not exclude each other. They need each other: memory brings depth and embodiment, technology brings rhythm and circulation. Their dialogue compels us to think of art not as a sacred sanctuary, but as an embodied and situated practice where every image is a negotiation between what was, what is, and what could be.

Accepting this hybrid condition also means accepting responsibility. It is not enough to produce beautiful images; we must make visible their provenance, their context, and their circulation. Only then will memory and technology cease to be feared as demons and instead reveal themselves for what they are: catalytic forces that expand how we remember and imagine together.